In 2005, Brendan Flynn, Irish Canadian Immigrant, and Dubliner Eddie Reynolds met at Eddie’s Merrion Square office, chatting about life in Canada. A stream of ‘Did you know’s?’ inevitably came up and it was agreed ‘We should acknowledge that!’ In May of that year, former President of Ireland, Mary McAleese, visited Vancouver and met local Irish. The visit inspired the Monument project.

Where to begin? Irish Canadian history began in 1536 when Canada’s first Irish settlers crossed the Atlantic and named the island we know today as Newfoundland, Talamh an Eisc (Land of Fish). In the 19th C thousands who fled the Great Hunger lost their lives to ‘coffin ship’ fevers and to the dangerous labour of building the Ontario canals. At the same time a ‘Miners Angel’ followed the gold rush north and several Religious Orders founded schools and hospitals. In 1867 the newly forming nation called forth four of Ireland’s finest as Founding Fathers of the Dominion of Canada. In the 20th C an Irish Colony was founded on the Prairies, an Irish-Canadian discovered insulin, there were the heroes of two world wars and Canada’s first flag, the grand Maple Leaf, was raised by an Irish-Canadian Prime Minister. Hurling became hockey. Toes were tapping to traditional Irish music. What did the Irish not do? A non-profit Society was formed in 2010 to proceed with the Ireland Canada monument project and Vancouver was chosen as the site to signify the nation-wide influence of the Irish. With the Vancouver Park Board cooperation and assistance, a park site was proposed. A second site adjacent to the waters of the Pacific ocean was offered. The twelve years of never giving up and working with the Vancouver Park Board had its reward, when a second ‘this was worth waiting for!’ site was offered.

The Luck of the Irish It was twelve years of never giving up and working with the Vancouver Park Board, when a second ‘this was worth waiting for!’ site was offered. The George Wainborn Park site, at Vancouver’s prime city-centre location on False Creek, is more than an idyllic, accessible location: it is amid the ancient ground of the Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh First Nations who have lived on the land known as Vancouver today since time immemorial. The history of Canada’s indigenous peoples resonates with many Irish and, as we reflect on our Irish history, we look forward to celebrating National Aboriginal Month this June for opportunities to learn more about and honour the heritage, contributions and cultures of Canada’s First Nations. National Aboriginal Day is June 21st. With deep respect and appreciation the Society acknowledges the powerful gift of ‘the green light’ that the Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh peoples have given the Ireland Canada Monument and indeed – the Irish in Canada.

The Public Process During the recent Public Process, the ICM Society submitted four designs completed by local Landscape design Architects PWL Consultants to the Park Board, two of which were selected specifically for the Public Process whereby local businesses and residents had the opportunity to share their opinions with the Parks Board. Whilst history records difficulties and differences, the Ireland Canada Monument Society project embraces the truth that to the Diaspora in Canada, Ireland is the island. Responses through the City of Vancouver website and Vancouver weekly and daily papers lean towards Plan A which, importantly, does not block the views for local residents. A path outlining the island of Ireland features entry points at Belfast, Dublin and Wicklow, Wexford, Waterford and, at the Galway/Clare entry, a walkway to the monument itself. It will be a truly leisurely walk for all visitors to the George Wainborn Park and an invitation to the Irish to revisit their roots.

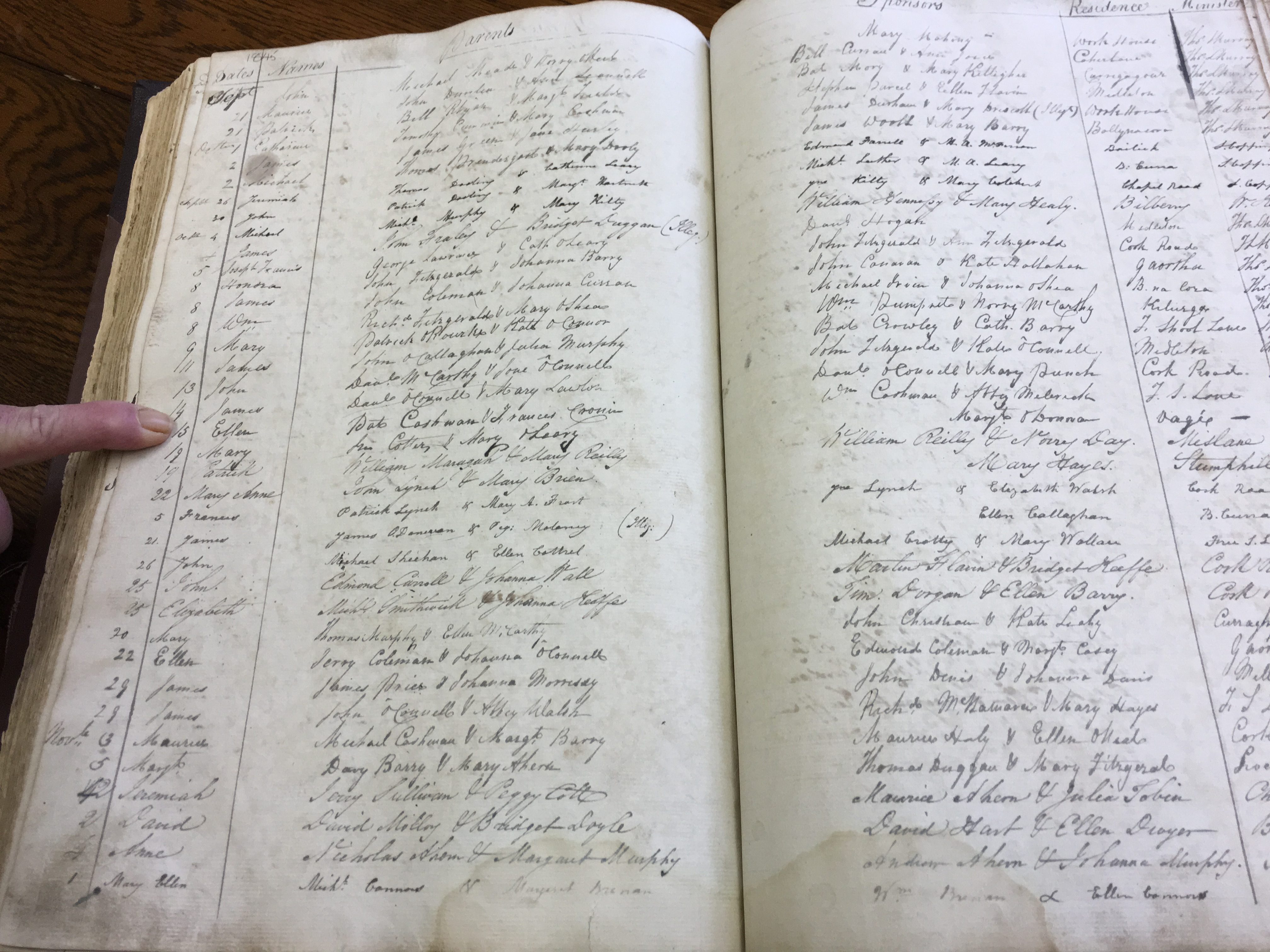

Irish Roots The 2011 Census reported more than 4-million descendants of Irish immigrants – 14% of the Canadian population. When they arrived in Canada (British North America) most Irish set aside their language to fit in but still many, scorned as ‘Famine Irish’, found themselves on the low steps of Canadian culture. Hundreds were cheap labour assigned to urban slums. Signs nailed to many public house doors read: No Blacks. No Dogs. No Irish. However, determined and excelling in diverse fields, the Irish at all levels of poverty and prosperity became a cultural force that brought to the fore values that significantly define what it means to be Canadian. On the waterfront, in the midst of Canadian greens, low monument walls are designed to be built with Ireland stonework and to bear names of many Irish immigrants and Irish-Canadians who have significantly contributed to Canada. The Ireland Canada Monument is a promise that as it stands, they will not be forgotten.

When you visit the Ireland Canada Monument look for these Monumental Irish D’Arcy McGee Born in Carlingford, 1825. At 17 years of age, he set sail for the United States and landed a job with a Boston newspaper. In 1845 Daniel O’Connell, impressed by a McGee editorial on Irish affairs, invited him to return to Ireland and join The Freeman’s Journal. The Ireland he returned to was an occupied English province. Within a year the blight wiped out the potato crops on which Irish tenant farmers had survived and, whilst the landlords shipped livestock, dairy and crops to England, one-fifth of the Irish died of starvation and more than a million emigrated in desperation. Charged with treason McGee escaped to North America where, in 1857, he was persuaded to settle his family in Canada and give voice to a new land where they might break through the racial and religious intolerance. He was elected one of three Members of Parliament for Montreal. He wrote three books on the history of Ireland and Irish settlements in North America and was the most popular and respected lecturer in Canada When the American Civil War broke out in 1861, Canadian colonies were at risk as incidents between the United States and Britain threatened war. Seeing the union of the colonies as vital McGee, the ‘fiery Celt’, crossed the floor to join Scotsman John A. MacDonald, Puritan George Brown and others, forming the coalition that negotiated an agreement with provision for the rights of minorities. In the 1867 election, McGee won his seat as a private member of the Parliament of the Dominion of Canada. In Ottawa, on the night of April 6, 1868, he made his last speech urging Nova Scotia to stay in confederation. It was after midnight when the House rose. Thomas D’Arcy McGee walked alone to the boarding house. As he turned the key in the lock, he fell, shot through the head. Ellen (Nellie) O’Kissane (Cashman) The Miners Angel Born in the farming village of Middleton, County Cork, in 1845. Her father died during the Great Hunger (ca.1850) and her mother emigrated with Nellie and her sister, Frances. They landed in Boston, moved to Washington, D.C. and on to San Francisco where her mother and sister remained. In 1874 Nellie followed the Gold Rush north to Cassiar, B.C. with 200 miners from Nevada. Settled in the remote region of Telegraph Creek, she set up a boarding house and mined her own claim. Her plan was to wait out the winter and collect supplies in Victoria, but there she heard that many of the men she had journeyed with were sick with scurvy. Nellie immediately hired six men and set out to go back and help them. The journey was 77 days long in the bitter cold, but they had managed to drag 1,500 lbs of supplies with them and they saved the men. The Daily British Colonist, 1875, described Nellie, “…a native of Ireland … possesses all the vivacity as well as the push and energy inherent in her race.” In Victoria the following winter, she learned that the city was building a hospital. On her return to Cassiar she ‘passed the hat’ and sent a substantial donation to the hospital. In 1898 Nellie once again joined the miners, climbing the Chilkoot Pass some 20 times to deliver the required supplies and help Fr. Judge, SJ to found St. Mary’s Hospital and welcome the Sisters of St. Ann who came to take on that work.

In the Autumn of 1924, Nellie came down with double pneumonia. Members of the Episcopal Church took her to St. Joseph’s Hospital in Victoria. She had ‘come home to die’ and there she was welcomed by the Sisters of St. Ann and Dr. Barrett who had, whilst in Dawson City, 1902, performed life-saving surgery on Nellie. Very much of Nellie’s financial success went to charities and, as it is reported by the Sisters of St. Ann, “One of Nellie’s less orthodox methods of raising funds for charitable causes was to slyly sneak into a large saloon and check out the various poker tables. When she saw a sizeable pot, and judged the participants to be agreeable, she would walk over to the table and put her arms around the money saying, ‘Now gentlemen, you don’t mind if this money goes to the good Christian women that’s taking care of the sick’.” Ellen (Nellie) Cashman died on January 4, 1925. She is buried beside the Sisters of St. Ann in Ross Bay Cemetery, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada

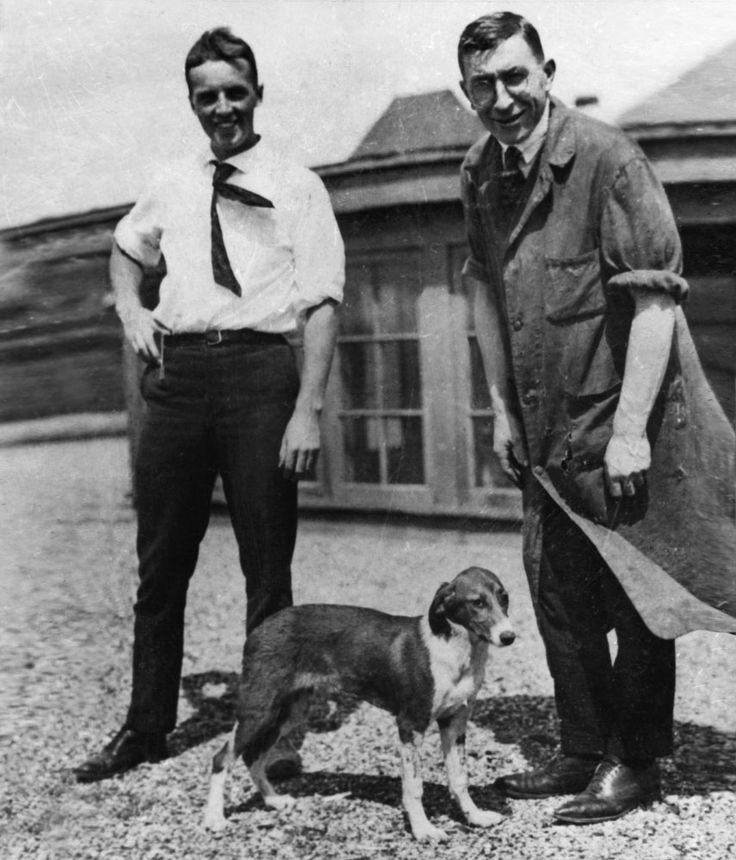

Sir Frederick Grant Banting Born in 1891 in the town of Alliston, north of Toronto, where his great grandparents, his grandparents and parents had moved from County Laois, Ireland. He was the youngest of five children in a hard-working middle-class farm family with a strong Methodist faith. Fred struggled to finish high school and failed first year Divinity at the U of Toronto. But he dreamed of becoming a doctor and persevered. In Sept. 1912, he was admitted to the U T Faculty of Medicine. Graduating in 1916 as the First World War was raging., he tried to sign up and was rejected twice because of poor eyesight. On his third try he was accepted into the Canadian Army Medical Corps. Just weeks before Armistice, he was wounded by an exploding German shell but kept on treating patients. For his bravery and determination under fire, he was awarded the Military Cross.

Following the war, Banting worked as a medical practitioner, resident surgeon for Sick Children, Toronto, part-time teacher in orthopaedics and lecturer in pharmacology. In 1922 he was awarded his M.D., together with a gold medal. Beyond his medical degree, he obt5ained the LL.D. (Queens) and the D.Sc. (Toronto). Deeply interested in diabetes and, determined to investigate the possibility of safely allowing insulin to be extracted, Banting consulted J.J.R. Macleod, Professor of Physiology at the U.of Toronto. Macleod gave him facilities for experimental work and Dr. Charles Best, a medical student, was appointed his assistant. The discovery of insulin won the Nobel Prize, which Banting shared with his assistant and other colleagues. It was one of the most important medical breakthroughs saving and transforming the lives of millions of people with diabetes. Among his many accomplishments and awards, Banting received the Reeve Prize of the U. of Toronto (1922). In 1923 the Canadian Parliament granted him a Life Annuity of $7,500. In 1928 Banting gave the Cameron Lecture in Edinburgh. He was appointed member of numerous medical academies and societies in Canada and abroad, including the British and American Physiological Societies, and the American Pharmacological Society. He was knighted in 1934. Not so well known is Banting’s artistic career. He described painting as ‘a great rest and holiday’. In 1927, Banting met A.Y. Jackson, of Canada’s ‘Group of Seven’, and a lasting friendship began. Over the years, they embarked on many painting excursions from the Coast to the Arctic. Asked about retiring from science to paint full time, Banting would reply, “When I am 50, that’s what I intend to do.” While en route to England on a military mission, Banting was killed in a plane crash near Musgrave Harbour, Newfoundland. He was forty-nine.

Loreena McKennitt born in Morden, Manitoba, 1957, she is a musician, composer, harpist, accordionist and pianist. She grew up in a happy rural environment wanting to become a veterinarian but she developed a passion for Celtic music and began busking at various places, including St. Lawrence Market, Toronto, to earn money to record her first album and the launch of a significant business. However, her passion for human rights is equally strong and, in 2006 and 2007 she was involved in a landmark human rights privacy case in Britain, where the courts ruled in her favour. The judgment, upheld by the House of Lords, has helped to advance privacy law around the world. McKennitt generously supports three charitable foundations which she established. Her Three Oaks Foundation provides financial support to cultural, environmental, historical and social groups. The Cook-Rees Memorial Fund for Water Search and Safety, and, in 2000, she purchased a recently-closed public school in Stratford and transformed it into the Falstaff Family Centre. Responding to concerns identified by the local community, the Centre focuses on the needs of families and children in Perth County, Ontario, which is where she resides. Loreena is a member of the Order of Canada and the Order of Manitoba. In 2002 and 2012 she was recipient of Queen Elizabeth II Golden & Diamond Jubilee medals, in 2013 she was appointed to the rank of Knight of the National Order of Arts & Letters by the Republic of France. From 2006 to 2013 she held the position of Honorary Colonel of the 435 Transport and Rescue Squadron in the Royal Canadian Air Force. Upon completion of the appointment McKennit was awarded the RCAF Commander’s Commendation in recognition of outstanding professionalism and dedication. She also holds honorary Doctorates from the University of Manitoba, Winnipeg Sir Wilfrid Laurier University (Waterloo), Queen’s University, Kingston, and Bachelor of Applied Business from George Brown College, Toronto.

We could go on a hundred times and more but let us refer you to our website which is still under construction and updates – www.irelandcanadamonument.com Please click on our Contact Us page to share your feedback or join us on Facebook.